Snowflakes: An Origin Story

And How to Become a Self-Actualized Adult

Attachment theory is a psychological, evolutionary, and ethological theory concerning relationships between humans formulated by psychiatrist and psychoanalyst John Bowlby in 1958 with further research by developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth. A child's attachment is largely influenced by their primary caregiver's sensitivity to their needs. Parents who consistently (or almost always) respond to their child's needs will create "securely attached" children. Such children are certain that their parents will be responsive to their needs and communications. A toddler who is "securely attached" to his or her parent will explore freely while the caregiver is present, typically engages with strangers, is often visibly upset when the caregiver departs, and is generally happy to see their caregiver return. The mainstream narrative is that "secure attachment" is the healthiest attachment type and produces well-rounded, psychologically healthy adults. And out of this theory emerged… helicopter parenting. The first mention of this parenting style appeared in 1969, but was more widely applied about a decade later. Generational demographer Neil Howe described helicopter parenting as the parenting style of Baby Boomer parents of Millennial children starting in the early 1980s.

So how did it turn out? Codependency is a behavioral and emotional condition in which a person becomes excessively reliant on another individual, typically someone who has an addiction or a compulsive behavior. In a codependent relationship, one person prioritizes the needs and desires of the other above their own, often to the detriment of their own well-being. Codependent individuals may have difficulty setting boundaries, expressing their own needs, and maintaining a separate sense of identity outside of the relationship. This pattern of behavior can lead to a cycle of enabling and dysfunctional dynamics within the relationship. That's the issue with overly "secure attachment" types (which, like the food pyramid, we were told is healthy). And that's the problem with most young people in our country today.

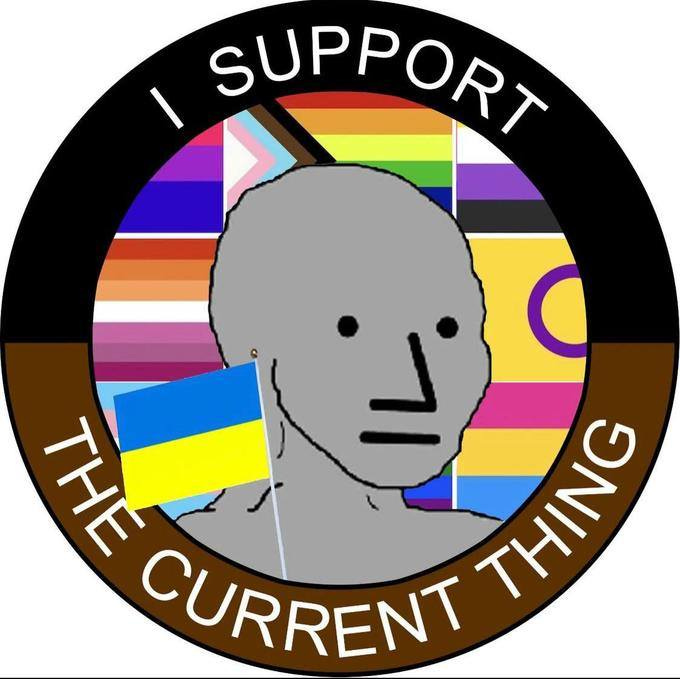

They are enmeshed in the identity of their marital relationships, political relationships, and governmental relationships because they grew up under helicopter parents who compulsively provided for all of their needs. Enmeshment involves low levels of autonomy or independence and high levels of inappropriate intimacy. Children who were enmeshed with helicopter parents became adults who don't know how to be their own person but rely on others to tell them who they are, what they believe, and how they feel. They become very upset when they're separated or dissonated from their enmeshed relationships, and thus they fear as adults being "cancelled" or having to entertain critical thought outside of the mainstream narrative. This is the snowflake generation. They are largely NPCs supporting whatever the mainstream narrative dictates, no matter how objectively preposterous.

On the other hand, Gen-Xers -- who were latchkey kids, whose parents told them to go outside in the morning and to come home when the street lights came on, and were chastised to stop crying and dust off their pants when they fell down -- developed insecure attachment types. Insecure attachment types enable people to be more independent, skeptical of relationships, and discerning about who they trust. This is a good thing so long as it isn't taken too far of course. Insecurely attached people are fine with throwing off toxic relationships or avoiding them in the first place and standing up for their own best interests. The mainstream narrative says that this is unhealthy though. Insecure attachment types are sometimes classified as attachment disorders!

Science has shown that mildly traumatic childhoods create highly achieving adults. Overcoming challenges is a part of the learning process. Research from Richard Tedeschi on Post-Traumatic Growth reveals how “negative experiences can spur positive change, including the recognition of personal strengths, the exploration of new possibilities, improved relationships, a greater appreciation for life, and spiritual growth.” People who have endured natural disasters, bereavement, job loss, economic stress, and serious illnesses often gain insight into themselves and the world in ways that transform their lives. In a study of 400 high achievers who had at least two biographies written about them (for positive reasons), it was found that 75% had experienced a difficult childhood. "Coping with stress is a lot like exercise: We become stronger with practice," explained clinical psychologist Meg Jay in The Wall Street Journal. Helicopter-parented snowflakes missed out on the opportunity to learn how to become self-actualized adults. No one would wish trauma or abuse on any child, but those who do weather these storms tend to learn extreme resilience, an outsized capacity to handle stress, and a dismissive attitude toward negative feedback. They largely become insecure attachment types.

Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s paper “A Theory of Human Motivation” posited that unsatisfied needs drive our behavior, and that basic needs such as physiological needs (air, water, food), safety, belongingness, and esteem must be met first, which is exactly what helicopter parents aimed to provide. Participation trophies for everyone! However, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (which is often illustrated in the shape of a pyramid with basic needs at the bottom and higher needs above) is topped with the need for self-actualization, or “the full realization of one’s potential,” and this is where helicopter parents stunted their children's development.

According to Maslow, characteristics of self-actualization include:

Appreciative: Self-actualized individuals maintain a sense of wonder and continued fresh appreciation for the ordinary aspects of life and everyday experiences.

Objective: They have an accurate, unbiased perspective or viewpoint, free from the distortions of personal feelings or opinions.

Authentic: They can maintain dignity and integrity even in environments and situations that are undignified.

Equanimous: They take life's inevitable ups and downs with grace, acceptance, and balance.

Accepting: They accept themselves, other people, and the natural world as they are, flaws included, without feeling the need to change them.

Autonomous: They are independent and self-sufficient, relying on their own judgment and accepting responsibility for their own lives without external approval or blame.

Resourceful: They have a strong ability to solve problems and find solutions to challenges that arise in their lives.

Individualist: They are spontaneous and creative, often expressing themselves in unique and original ways, without feeling pressured to be how others want them to be.

Contemplative: They enjoy spending time alone and often find solitude to be rejuvenating rather than isolating.

Ethical: They have a strong sense of ethics and morality, guided by principles of honesty, integrity, and fairness.

Humanitarian: They have a deep sense of empathy and compassion for others, often working to promote the welfare and happiness of humanity as a whole.

Purpose-driven: They feel a great responsibility and duty to accomplish a particular mission in life, usually focused outward.

Interconnected: They form profound interpersonal relationships with others, based on mutual respect, trust, and understanding.

Lighthearted: They have a healthy sense of humor, able to laugh at themselves and the absurdities of life.

Transcendent: They frequently have moments of intense joy, ecstasy, or transcendence, which Maslow called "peak experiences".

A healthy middle ground between codependency and total independence is interdependency, which is a form of voluntary and provisional dependency that is mutual with another person or institution in a way that is mutually beneficial and not destructive. This is what we should strive to achieve to experience the full benefits of social relationships -- sufficiently avoidant-dismissive to reject bad relationships, sufficiently secure to embrace good ones, and sufficiently anxious to know the difference. When we achieve that, then we can be self-actualized, having a healthy mix of independence and deep connection.

Although it may be difficult for parents, the best way for people to start down the path to self-actualization is by being allowed to make mistakes and even get hurt as a child. There was a time when parents said that the best way to teach a child not to touch a hot stove is to let them touch a hot stove. And whatever doesn't kill you makes you stronger. As George Carlin joked 20 years ago regarding the unhealthy fear of germs in society, "When I was a little boy... we swam in the Hudson River... and it was filled with raw sewage... [but] in my neighborhood nobody ever got polio ever because we swam in raw sewage. It strengthened our immune systems. The polio never had a prayer. We were tempered in raw shit." That may or may not be embellished for dramatic effect, but we have to allow ourselves and our children to be exposed to challenges, distress, and discomfort so as to grow stronger as a result. Children may cry, so might adults. Let it out and move past it. Learning NOT to trust that your parents (or your government or your spouse) will always prevent harm or make it all better is an important lesson. You have to assess risks and rewards using your own faculties of judgment and accept responsibility for the outcome. It might make you feel a little insecure, but that's okay. That's healthy. It's a signal to take action. We cure insecurity with preparedness and competence and healthy relationships, not ignorance and denial and codependency.